The latest exhibit at the Art Gallery of Grande Prairie (AGGP) has about 200 dolls lining the walls of its exhibit spaces. Unlike most dolls, these do not have faces.

The Faceless Doll Project, a partnership between the gallery and the Grande Prairie Friendship Centre (GPFC), is a way to honour and remember the child victims of Canada’s residential school system.

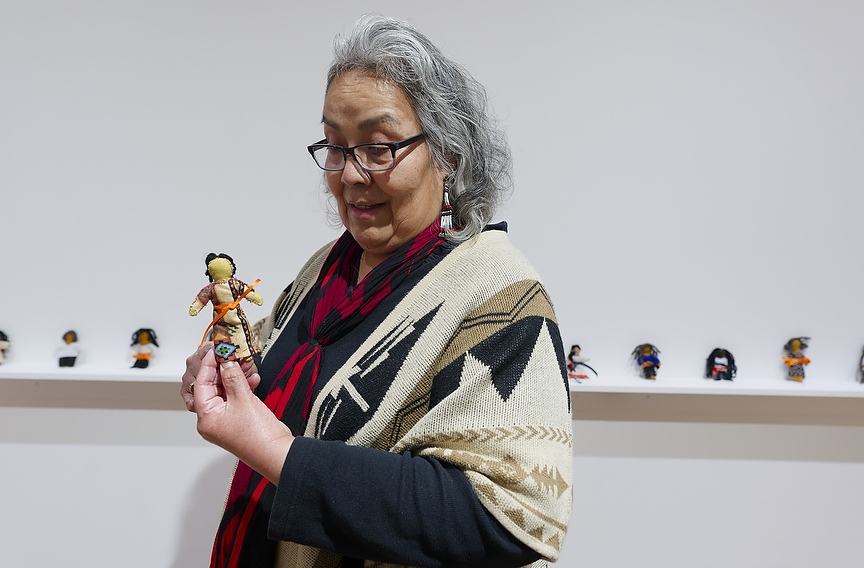

“Once you put a face on something, it gives them spirit,” said Elder Loretta Parenteau-English, who started the project.

The workbegan in June 2021 after the discovery of 215 unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Faces and eyes are not used in some indigenous art including regalia, because they give the object life, explained Parenteau-English.

The faceless dolls also have a sense of anonymity and don't represent a single person but the many indigenous children who died in residential schools, who may not be identified.

“When I heard about the children that were found in Kamloops, I felt really sad that they didn't have the opportunity to be with their parents, you know, just to share what I shared with my mom and dad for the first 10 years of my life,” she said.

Parenteau-English reminisced about how her father would make dolls for her from wire and cloth or plywood, using scraps of fabric from her mother’s sewing, and she would sew their clothes.

She had about 15 dolls when her father passed away when she was 10.

Living in a four-room house with 14 children, her mother and grandparents struggled after the passing of her father. One day, to keep the house warm, the dolls had to be burned.

After the discovery in Kamloops, Parenteau-English reflected on how those children didn’t have the opportunity to be with their parents or have the benefit of having parents give them dolls.

Parenteau-English then made two dolls and spoke to GPFC program co-ordinator Natascha Okimaw about creating 215 dolls to honour the children.

Okimaw began gathering all the required materials.

The duo then began making dolls with the GPFC Wahkotowin seniors group. Parenteau-English shared about her experience at residential schools; other elders would also share their stories as they worked.

The project soon expanded to other senior groups and Parenteau-English shared her story with local high schools and had students help make some too.

Lindsy Coney, GPFC Pitone youth program co-ordinator, said that many students used extracurricular time to finish the dolls and add them to the collection.

“We've had lots of teachers reach out,” said Coney.

“We had youth in grades nine to 12 work on faceless dolls, so the collection that you see upstairs is from the project that was initially started with the seniors and the youth and then carried on by the high school students.”

The exhibit dolls are a mixture of boys and girls: Little tea dresses and pants and shirts adorn the figures.

“Pretty similar to what a child would have worn in residential school, but we wanted to have the prints to still represent indigenous culture, so a lot of the dresses have little flowers on them to represent the kokum spirit,” said Okimaw.

“We have included the orange ribbon in there to represent Every Child Matters, and then when we were stuffing them, we wanted to include a little piece of sage to give them some medicine.”

On Thursday, community members gathered at the gallery to contribute to the exhibit by creating their own faceless dolls.

“It felt good that we can all come together and do something together,” said Parenteau-English.

“It takes the whole community to build this project; we can't do it alone.”

Upon seeing the exhibit for the first time after its installation on Thursday, Parenteau-English found the first doll she created.

She said she could never have imagined all the work it would take to get to this point.

After the exhibit closes, the dolls will be moved to the GPFC Traditional Healing Garden, where they will be permanently displayed.

Okimaw hopes to have a display near the medicine wheel in the garden before the fall.

“It's a good reminder to people that we're still here … and how resilient we are as people, and it gives that space for those that need to continue with their healing and their journey,” said Okimaw.

The exhibit will have a closing reception on February 15 at 2 p.m. at AGGP.