Local paleontologists may have unearthed the largest dinosaur skull to come from the Pipestone Creek bonebed last Wednesday.

The 72-million-year-old, 1.6 metre-long, 272-kilogram skull of a pachyrhinosaurus lakustai, a dinosaur unique to the Grande Prairie region, is the first skull to be retrieved from the bonebed in about 16 years.

“This is definitely the biggest fossil I've ever had an opportunity to work on,” said Emily Bamforth, Philip J. Currie Museum (PJCDM) curator.

“Every fossil we find is unique.

“Every fossil from the bonebed or from anywhere, really, can tell you something unique about that animal that lived in that time period.

“It is particularly true of skulls; a dinosaur skull has an incredible amount of information.”

She said there is a possibility of recreating the dinosaur's brain with information from the skull, which can give more insights into the dinosaur's cognition, sense of smell, hearing and social interactions.

She also noted it would give paleontologists a better understanding of certain species and their differences since there are very few samples to compare.

Bamforth and her team have spent much of the summer preparing to remove the skull, removing other bones around it (about 300), and digging around it to place it on a pedestal, then adding plaster to make a field jacket.

Once the plaster is hardened, it is flipped to be plastered and protected for the move.

Last Wednesday, the group of paleontologists from PJCDM were busy digging around the skull, and preparing for the flip.

“A lot can go wrong with a flip of a jacket this size,” said Bamforth.

She said there are two scenarios that she feared: “The first thing is, that there is bone going into the ground that you don't know is there, so when you flip it out, that stays in the ground, and the rest of the fossil goes with the jacket; that's not a good scenario.

“The other thing you really don't want to happen is for you flip it over, and the rock starts to break under the jacket, and it pours out the bottom, and then you lose the support that's holding up the bone, so the bone starts pouring out as well.

“That's every paleontologist's worst nightmare.”

When the digging stopped and the preparations to begin the flip began, Bamforth noted her heart was beating quickly.

They were attempting the flip with a crane and pry bars but the fossil began to slightly slide, which could cause fear number two to become true.

The crew stopped, adjusted their strategy and flipped the skull by hand with the help of onlookers.

“I'm so relieved that it went really well,” said Bamforth.

The flip revealed some more fossils, a rib bone, a seed, and part of a tree, all of which the museum’s research and collections technician Jackson Sweder quickly began preparing for the move back to the museum.

Bamforth quickly began mixing up the plaster and within minutes many hands began to plaster the exposed fossil.

The skull was then lifted and placed on a large cart to make its way down a trail to a waiting truck and trailer.

A crew slowly made their way down the hill on the trail, wet from a rain earlier in the morning.

Aster, the resident Paleo Pooch, helped lead the way. Although most days she would lounge around the dig site and let the paleontologists know of people coming to the dig site - or even scare off the occasional bear - today she was leading the way.

Big Sam, as the skull has been nicknamed by museum staff, was then put onto a trailer and transported to the lab in the museum.

Discovery of Big Sam

The museum first discovered Big Sam when they found what they thought was a piece of skull last summer.

“We got really excited; we thought we had an isolated brain case, which is something we have found from the bonebed previously,” said Bamforth.

They then continued their digging and found more skull bones. Then in October last year they realized all the bones were connected.

“Unfortunately, it was October, it was already snowing, and so it was way, way too late to actually get it out of the ground that year,” said Bamforth.

The paleontologists then plastered what they had found and buried it until winter ran its course.

When the crew returned this summer they began working on their find, removing the cap rock, a really hard rock that sits just above the bone layer.

“We realized the skull was a lot bigger than we thought it was.” About 300 other bones were jammed against the skull.

It took the paleontolgists about four months to clear all the bones and then prepare the skull for its move on Sept. 25.

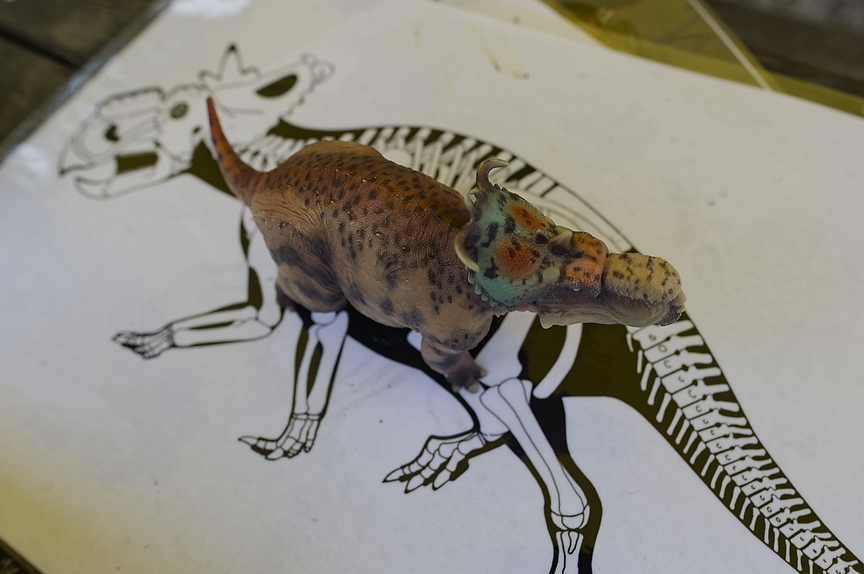

Bamforth said pachyrhinosaurus lakustai are endemic to the Grande Prairie region; other species of it can be found in Southern Alberta and Alaska.

Pachyrhinosaurus lakusta is named after Al Lakusta, who found the first fossils in Pipestone Creek back in the 1970s.

Grande Prairie’s pachyrhinosaurus lakusta had unique features, such as a spike in the middle of its forehead. “We call the unicorn spike that's unique to our species,” said Bamforth.

“Our species also has a particular arrangement of horns on the back of its frill, and also, unlike the other two species of pachyrhinosaurus, ours has got a big bony bump on the nose called a boss and then separate bosses over the eyes, whereas the other two species, all of those bosses are kind of glommed together into a huge boss.”

Future of Big Sam

Big Sam will now reside in the museum, where technicians will begin preparing the skull. People will be able to follow their progress from the viewing deck in the museum.

“We eventually hope to have it out on display in our gallery,” said Bamforth, adding it could take more than a year and year half.

“The Pipestone Creek bonebed is unique in the world; it's one of the densest dinosaur bonebeds in North America,” she said.

“It contains a single community of a single species of dinosaur from a snapshot in time, which is unprecedented in the fossil record.”

The creation of the bonebed is still a mystery but some theories exist.

It’s believed that the pachyrhinosaurus was a “super herd” animal, that lived in small groups and then would migrate as a large group of possibly thousands.

“One terrible day, 72 million years ago, something comes in and wipes out the whole herd,” said Bamforth.

“What killed them is actually still a mystery, we don't know because a second event basically came in and erased all of that evidence from the first event.

“Our speculation right now is they died in some kind of a flooding event, like they're trying to cross a flooded river, or were caught in a flash flood, or maybe a mudslide, something like that.

Whatever it was, it wiped out the whole herd, the old ones, the young ones, the big ones, the small ones. Everyone died.”

Evidence based on this is that scavengers eventually came and ate the pachyrhinosaurus, leaving teeth and bones behind.

The second event was a flood that moved all the bones into a channel, creating a giant pile of bones that paleontologists now are discovering.